A cancer is an uncontrolled proliferation of cells.

- In some the rate is fast; in others, slow; but in all cancers the cells never stop dividing.

- This distinguishes cancers — malignant tumors — from benign growths like moles where their cells eventually stop dividing (usually). Even more important, benign growths differ from malignant ones in not producing metastases; that is, they do not seed new growths elsewhere in the body.

- Cancers are clones. No matter how many trillions of cells are present in the cancer, they are all descended from a single ancestral cell. Evidence: Although normal tissues of a woman are a mosaic of cells in which one X chromosome or the other has been inactivated [Link], all her tumor cells — even if from multiple sites — have the same X chromosome inactivated.

-

Cancers begin as a primary tumor. Most (maybe all) solid tumors shed cells into the lymph and blood. Most of these lack the potential to develop into tumors. However, some of the shed cells are able to take up residence and establish secondary tumors — metastases — in other locations of the body. These metastases, not the primary tumor, are what usually kills the patient.

- Cancer cells are usually less differentiated than the normal cells of the tissue where they arose. This process of dedifferentiation results in the cells of the growing tumor taking on the attributes of stem cells. In addition some cancers actually arise in precursor cells — stem cells or "progenitor cells" — of the tissue: cells that are dividing by mitosis producing daughter cells that are not yet fully differentiated (see below).

Cancer cells contain many mutated genes, in some cases over 100. Most of these are "passenger" mutations probably having no effect on the malignant process. They are just as likely to be found in healthy cells. However tumor cells also contain a small number (2–8) of mutant genes that are found so frequently in tumors that they are probably responsible for the malignancy. These are called "driver" mutations.

Some 300 driver mutations have been identified. These fall into several categories.

- Mutations in genes that are involved in cell survival; that is,

-

genes that promote mitosis.

The mutated or over-expressed products of these genes, called oncogenes, drive the malignant process stimulating mitosis even though normal growth signals are absent.

Example: EGFR, the gene encoding the receptor for epidermal growth factor (EGFR). (EGFR is also known as HER1.)

Oncogenes act as dominants; that is, only one of the pair need be over-expressed or mutated to predispose the cell to cancer.

- genes that inhibit the normal death of damaged cells by apoptosis. Mutations in these enable the cell to ignore signals telling it that it is irreparably damaged and should commit suicide.

- Mutations in genes that are responsible for maintaining the integrity of the cell's genome, e.g., DNA repair genes.

Example: the TP53 gene product normally senses DNA damage and either halts the cell cycle until it can be repaired or, if the damage is too massive, triggers apoptosis.

The normal unmutated version of TP53 inhibits malignant transformation and thus is an example of a tumor suppressor gene.

Tumor suppressor genes are recessive; that is, either both copies must be mutated for their function to be lost or — more commonly — the healthy copy of the gene has been lost [More].

- Mutations in genes that regulate cell fate; that is, the pathway of differentiation down which a cell travels. Differentiated cells have usually exited the cell cycle and begin to perform their function until they die. Mutated genes that interrupt differentiation and promote continued cell division can increase the risk of tumor formation.

Examples of such genes are NOTCH and Sonic hedgehog (SHH) as well as genes that make epigenetic modifications in chromatin, e.g., by methylating histones or DNA.

- Mutations in genes that stimulate angiogenesis. Tumors, like any tissue, need a blood supply to bring food and oxygen and to take away wastes. So as it grows, a developing cancer must be able to stimulate the growth of new blood vessels into itself. This is done by the release of angiogenesis stimulants, e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), the product of the tumor suppressor gene VHL.

What probably happens is:

- A single cell — perhaps an adult stem cell or progenitor cell — in a tissue suffers a mutation (red line) in a gene involved in the cell cycle, e.g., an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene.

- This results in giving that cell a slight growth advantage over other dividing cells in the tissue.

- As that cell develops into a clone, some if its descendants suffer another mutation (red line) in another cell-cycle gene.

- This further deregulates the cell cycle of that cell and its descendants.

- As the rate of mitosis in that clone increases, the chances of further DNA damage increases.

- Eventually, so many mutations have occurred that the growth of that clone becomes completely unregulated.

- The result: full-blown cancer. (Genetic analysis reveals an average of 63 mutations in pancreatic cancers; almost as many in one type of adult brain cancer, but only 11 somatic mutations in a case of brain cancer in a child.)

- Sequencing samples from several areas in a primary tumor, as well as from some of its metastases, reveals a different collection of mutations from sample to sample. This finding is reinforced by the sequencing of the genome of individual cells from a single tumor each of which shows a unique pattern of shared and unique mutations. (The ability to sequence the genome of a single cell reveals that even normal cells in an adult have accumulated a suite of somatic mutations that differs from cell to cell. However, the rate of somatic mutations in these normal cells is only a fourth of that in cancer cells.)

So even though all the malignant cells in a cancer are descended from a single original cell — and thus are members of a single clone — they are no longer genetically-identical. As the tumor develops, its various cells develop a variety of additional mutations, and these give rise to "subclones" of varying degrees of malignancy with varying

- propensity to metastasize;

- susceptibility to treatment by anticancer drugs;

- propensity to relapse after apparently-successful therapy.

These findings should stimulate a reexamination of the use of chemotherapy.

- While chemotherapy may wipe out dominant subclones in a tumor, there is evidence that is also exerts a selective pressure for the expansion of more malignant, previously-minor, subclones.

- Most chemotherapeutic agents damage DNA [Link] so while killing off some cells, they will raise the mutation rate in any surviving cells perhaps encouraging the outgrowth of even more malignant subclones.

Evidence: In a group of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, those receiving chemotherapy survived for shorter periods than those that did not.

Cancer Stem Cells

Stem cells are cells that divide by mitosis to form either

- two stem cells, thus increasing the size of the stem cell "pool",

or

- one daughter that goes on to differentiate, and

one daughter that retains its stem-cell properties.

There is growing evidence that most of the cells in leukemias, breast, brain, skin, ovarian, and colon cancers are not able to proliferate out-of-control (and to metastasize). Only those members of the clone that retain their stem-cell-like properties (~2.5% of the cells in a tumor of the colon) can do so.

There is a certain logic to this. Most terminally-differentiated cells have limited potential to divide by mitosis and, seldom passing through S phase of the cell cycle, are limited in their ability to accumulate the new mutations that predispose to becoming cancerous. Furthermore, they often have short life spans — being eliminated by apoptosis (e.g., lymphocytes) or being shed from the tissue (e.g., epithelial cells of the colon). The adult stem cell pool, in contrast, is long-lived, and its members have many opportunities to acquire new mutations as they produce differentiating daughters as well as daughters that maintain the stem cell pool.

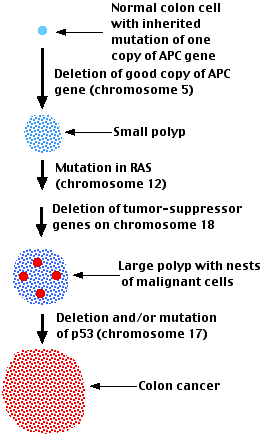

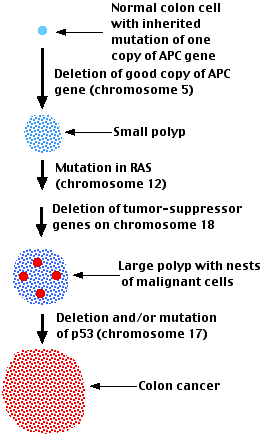

Colon cancer:

Colon cancer:

- begins with the development of polyps in the epithelium of the colon.

Polyps are benign growths.

- As time passes, the polyps may get bigger.

- At some point, nests of malignant cells may appear within the polyps

- If the polyp is not removed, some of these malignant cells will escape from the primary tumor and metastasize throughout the body.

Examination of the cells at the earliest, polyp, stage, reveals that they contain one or two mutations associated with cancer. Frequently these include- the deletion of a healthy copy of the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene on chromosome 5 leaving behind a mutant copy of this tumor suppressor gene

Two results:

- One of the functions of the APC gene product is to destroy the transcription factor β-catenin thus preventing it from turning on genes that cause the cell to divide [Link]. With no, or a defective, APC protein, the normal brakes on cell division are lifted.

- Another function of the APC protein is to help attach the microtubules of the mitotic spindle to the kinetochores of the chromosomes. With no, or a defective, APC product available, chromosomes are lost from the spindle producing aneuploid progeny.

- a mutant oncogene (often RAS).

- deletion and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53

Note that each of the mutations shown probably occurs in one cell of the type affected. This cell then develops into the next stage of the progression. The mutations do not necessarily occur in the order shown, although they often do.

The cells in the later stages of the disease show a wide variety of additional mutations including point mutations, deletions, translocations, and duplications. A handful (2–8) of these are "driver" mutations playing significant roles in the malignancy. The others are probably "passenger" mutations that play no role in the process.

A similar stepwise genetic progression occurs in

It is becoming clear that this is what one should expect. What distinguishes one cancer from another is not the tissue of origin, but the particular accumulation of mutations that drive its growth. Once these are identified, it will eventually be possible to choose chemotherapeutic agents that target the particular pathways in a given cancer — personalized therapy. [Link to an example.]

Over a lifetime, men are half-again more likely to develop cancer than women. This effect seems not to be caused by any differences in lifestyle or exposure to carcinogens.

Why this bias?

One possibility is the presence of a few tumor suppressor genes on the X chromosome. As men have only a single X chromosome, they have only one copy of each of these tumor suppressor genes and thus a mutation in one of them would remove the brake on tumor formation. Women, with their two X chromosomes, would still have a functioning copy.

But there is a problem with this explanation. The phenomenon of X-chromosome inactivation causes every cell in the woman's body to contain one active and one inactive X chromosome seemingly putting her in the same situation as males. As it turns out, however, not all the genes on the inactive chromosome are actually inactive. Some 50 of the approximately 800 genes on the X chromosome continue to be active and these include some tumor suppressor genes. So females retain their advantage in avoiding cancer.

The graph shows the death rate from cancer in the United States as a function of age. The graph can best be explained by the need for an accumulation of several "hits" to genes that control the cell cycle before a cell can become cancerous.

Sequencing of the genomes of a sample of single cells from different parts (including metastases) of a tumor in a single patient reveals in each a suite of mutations some of which are found in all samples, others in some, others in only a single sample. The gene or genes found in all samples represent those that began the malignant process. Estimating the mutation rate in these clones and subclones indicates that these tumors actually got their start 20–30 years before.

The graph also explains why cancer has become such a common cause of death during the twentieth century. It probably has very little to do with exposure to the chemicals of modern living and everything to do with the increased longevity that has been such a remarkable feature of the 20th century. A population whose members increasingly survive accidents and infectious disease is a population increasingly condemned to death from such "organic" diseases as cancer.

Cancers are caused by

- anything that damages DNA; that is anything that is mutagenic

- radiation that can penetrate to the nucleus and interact with DNA

- chemicals that can penetrate to the nucleus and damage DNA. Chemicals that cause cancer are called carcinogens.

- agents that cause inflammation (which generates DNA-damaging oxidizing agents in the cell)

- certain other chemicals; some the products of technology [example]

- anything that stimulates the rate of mitosis. This is because a cell is most susceptible to mutations when it is replicating its DNA during the S phase of the cell cycle.

- certain hormones (e.g., hormones that stimulate mitosis in tissues like the breast and the prostate gland)

- chronic tissue injury (which increases mitosis in the stem cells needed to repair the damage)

- certain viruses

(Considering that from conception to death, an estimated 1016 mitotic cell divisions occur in humans, it is remarkable that cancer is not more common than it is!)

Many viruses have been studied that reliably cause cancer when laboratory animals are infected with them. What about humans?

The evidence obviously is indirect but some likely culprits are:

- two papilloma viruses that can cause cancer of the cervix and other regions of the genitals (male as well as female).

- the hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses, which infect the liver and are closely associated with liver cancer (probably because of the chronic inflammation they produce)

- some herpes viruses such as the Epstein-Barr virus (implicated in Burkitt's lymphoma) and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) which is associated with Kaposi's sarcoma (a malignancy frequently seen in the late stages of AIDS)

- two human T-cell lymphotropic viruses, HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 [Link]

But note! Clearly viral infection only contributes to the development of cancer.

- Many people are infected by these viruses and do not develop cancer.

- When cancers do arise in infected people, they still follow our rule of clonality. Many cells have been infected, but only one (usually) develops into a tumor.

So again it appears that only if an infected cell is unlucky enough to suffer several other types of damage will it develop into a tumor.

Nevertheless, widespread vaccination against these viruses should not only prevent disease but lower the incidence of the cancers associated with them.

- A vaccine against hepatitis B is available as are

- two vaccines (Gardasil® and Cervarix®) against the most dangerous papilloma viruses.

The short answer is NO.

The reason: Cancer cells, like all cells in the body, express histocompatibility molecules on their surface. So like any organ or tissue transplant between two people (other than identical twins), they are allografts and are recognized and destroyed by the recipient's immune system [Link].

However, there are some exceptions.

- Although tumors are not transmissible, viruses are. So any of the viruses described in the previous section can be spread from person to person and predispose them to the relevant cancers.

- There have been a number of cases where, unbeknownst to the surgeon, an organ (e.g., a kidney) from a donor with melanoma has allowed the growth of the same melanoma in the recipient. Transplant recipients must have their immune system suppressed if the transplant is not to be rejected, but their immunosuppression also prevents their immune system from attacking the melanoma cells. Stopping immune suppression cures the recipient (but also causes loss of the kidney).

- Canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT). This tumor spreads from dog to dog during copulation. Although MHC molecules are only weakly expressed on the tumor cells, they do eventually cause the tumor to be rejected.

- Devil facial tumor disease (DFTD). The carnivorous Tasmanian devil is a marsupial living in Tasmania, Australia. The population is threatened by a facial cancer that is spread through bites. The population is highly inbred, thus closely-related genetically, and Class I MHC molecules are not expressed on the tumor cells. So it may be these factors that allow the tumor to grow unchecked.

- The soft-shell clam, Mya arenaria, along the North Atlantic coast of North America is being devastated by a leukemia that spreads from animal to animal perhaps as these filter feeders ingest sea water in which leukemic cells have been shed. These mollusks are invertebrates and lack powerful tissue rejection molecules like the MHC of vertebrates.

- There are extremely rare cases where a pregnant woman with cancer (usually leukemia, lymphoma or melanoma) has transmitted the cancer across the placenta to her fetus (whose immune system has yet to develop). In the months after they are born, they may succumb to the disease, but occasionally, an infant will be able to reject the cancer.

In the year 2000 Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg published a paper — The Hallmarks of Cancer — outlining 6 characteristics that are acquired as a cell progresses toward becoming a full-blown cancer. In the 4 March 2011 issue of Cell, they add 4 other features.

- Uncontrolled proliferation. See above.

- Evasion of growth suppressors. Among the many mutations found in cancers, one or more inactivate tumor suppressor genes. [Link to a discussion.]

- Resistance to apoptosis (programmed cell death). Link to a discussion.

- Develop replicative immortality; i.e., avoid the normal process of cell senescence. Link to a discussion.

- Induce angiogenesis; that is, promote the development of a blood supply. Link to a discussion.

- Invasion and metastasis — the ability of tumor cells to invade underlying tissue and then to be carried to other parts of the body where secondary tumors develop (metastasis). During this process, the normal adhesion of cells to each other and to the underlying extracellular matrix (ECM) are disrupted.

- Genomic instability. Cancer cells develop chromosomal aberrations and many (hundreds) of mutations. Most of the latter are "passenger" mutations, but as many as 10 may be "drivers" of the cancerous transformation.

- Inflammation. Tumors are invaded by cells of the immune system, which promote inflammation. One effect of inflammation is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These damage DNA and other molecules.

- Changed energy metabolism. Even if well-supplied with oxygen, cancer cells get most of their ATP from glycolysis not cellular respiration.

- Evade the immune system. This is described in the page Immune Surveillance. Efforts to manipulate the immune system to combat cancer are described in the page Cancer Immunotherapy.

All cancers are genetic diseases characterized by an uncontrolled proliferation of their cells.

These cells arose from a single cell that began to lose control of its rate of division because of an accumulation of certain mutated genes (DNA).

A cell destined to give rise to a cancer can have acquired the mutations

- by inheritance (e.g., APC, BRCA1)

- spontaneously — mutations that arise every time the over 6 billion “letters” of our DNA are copied in preparation for making two cells from one. This explains why cancers are more common in tissues that have high rates of cell division (e.g., blood) than in tissues that do not (e.g., heart).

Although copying DNA is remarkably accurate, every newly-formed cell probably contains some 3 new errors (mutations). Most of these (“passenger” mutations) occur in regions of our DNA that play no role in cell division. But mutations (“driver” mutations) in two dozen or so genes that do control cell division can propel the cell along the path to cancer.

- induced by external (environmental) agents that increase the rate of mutation. These include:

- agents that damage DNA directly such as chemotherapy drugs, radiation, and DNA-damaging agents released in response to inflammation.

- agents that increase cell division in a tissue. (e.g., infection by human papilloma virus.)

- both (e.g., tobacco smoke)

Current estimates are that only one-third of human cancers arise from category 3 and thus could be avoided by changes in life-style (e.g., smoking, diet, workplace safety). The rest (two-thirds) are "bad luck".

11 January 2021

Colon cancer:

Colon cancer: