In eukaryotes, chromosomes consist of a single molecule of DNA [Link to visual proof] associated with:

- For most of the life of the cell, chromosomes are too elongated and tenuous to be seen under a microscope.

- Before a cell gets ready to divide by mitosis, each chromosome is duplicated (during S phase of the cell cycle).

- As mitosis begins, the duplicated chromosomes condense into short (~ 5 µm) structures which can be stained and easily observed under the light microscope.

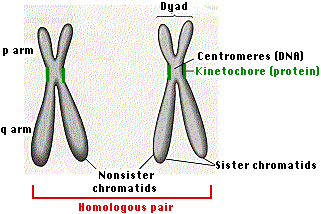

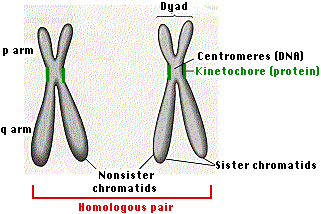

- These duplicated chromosomes are called dyads.

- When first seen, the duplicates are held together at their centromeres. In humans, the centromere contains 1–10 million base pairs of DNA. Most of this is repetitive DNA: short sequences (e.g., 171 bp) repeated over and over in tandem arrays.

- While they are still attached, it is common to call the duplicated chromosomes sister chromatids, but this should not obscure the fact that each is a bona fide chromosome with a full complement of genes.

- The kinetochore is a complex of >80 different proteins that forms at each centromere and serves as the attachment point for the spindle fibers that will separate the sister chromatids as mitosis proceeds into anaphase.

- The shorter of the two arms extending from the centromere is called the p arm; the longer is the q arm.

- Staining with the trypsin-giemsa method reveals a series of alternating light and dark bands called G bands.

- G bands are numbered and provide "addresses" for the assignment of gene loci.

- All animals have a characteristic number of chromosomes in their body cells called the diploid (or 2n) number.

- These occur as homologous pairs, one member of each pair having been acquired from the gamete of one of the two parents of the individual whose cells are being examined.

- The gametes contain the haploid number (n) of chromosomes.

(In plants, the haploid stage takes up a larger part of its life cycle - Link)

Diploid numbers of some commonly studied organisms

(as well as a few extreme examples)

| Homo sapiens (human) | 46

|

| Mus musculus (house mouse) | 40 |

| Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) | 8 |

| Caenorhabditis elegans (microscopic roundworm) | 12 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast) | 32 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (plant in the mustard family) | 10 |

| Xenopus laevis (South African clawed frog) | 36 |

| Canis familiaris (domestic dog) | 78 |

| Gallus gallus (chicken) | 78 |

| Zea mays (corn or maize) | 20 |

| Muntiacus reevesi (the Chinese muntjac, a deer) | 23 |

| Muntiacus muntjac (its Indian cousin) | 6 |

| Myrmecia pilosula (an ant) | 2 |

| Parascaris equorum var. univalens (parasitic roundworm) | 2 |

| Cambarus clarkii (a crayfish) | 200 |

| Equisetum arvense (field horsetail, a plant) | 216 |

The complete set of chromosomes in the cells of an organism is its karyotype. It is most often studied when the cell is at metaphase of mitosis and all the chromosomes are present as dyads.

The karyotype of the human female contains 23 pairs of homologous chromosomes:

The karyotype of the human male contains:

- the same 22 pairs of autosomes

- one X chromosome

- one Y chromosome

(A gene on the Y chromosome designated SRY is the master switch for making a male.)

The X and Y chromosomes are called the sex chromosomes.)

Above is a human karyotype (of which sex?). It differs from a normal human karyotype in having an extra #21 dyad. As a result, this individual suffered from a developmental disorder called Down Syndrome. The inheritance of an extra chromosome, is called trisomy, in this case trisomy 21. It is an example of aneuploidy

This image (courtesy of David C. Ward) provides dramatic evidence of the truth of the story of chromosomes. A piece of single-stranded DNA was prepared that was complementary to the DNA of the human gene encoding the enzyme muscle glycogen phosphorylase. A fluorescent molecule was attached to this DNA. The dyads in a human cell were treated to denature their DNA; that is, to make the DNA single-stranded. When this preparation was treated with the fluorescent DNA, the complementary sequences found and bound each other. This produced a fluorescent spot close to the centromere of each sister chromatid of two homologous dyads (of chromosome 11, upper right). This analytical procedure, which here revealed the gene locus for the muscle glycogen phosphorylase gene, is called fluorescence in situ hybridization or FISH.

The molecule of DNA in a single human chromosome ranges in size from 50 x 106 nucleotide pairs in the smallest chromosome (stretched full-length this molecule would extend 1.7 cm) up to 250 x 106nucleotide pairs in the largest (which would extend 8.5 cm).

Stretched end-to-end, the DNA in a single human diploid cell would extend over 2 meters.

In the intact chromosome, however, this molecule is packed into a much more compact structure. [Link]. The packing reaches its extreme during mitosis when a typical chromosome is condensed into a structure about 5 µm long (a 10,000-fold reduction in length).

Structural Abnormalities of Chromosomes

There are a number of agents — both exogenous (e.g., ionizing radiation) and endogenous (e.g., crossing over in meiosis) — that break the double helix of DNA. Often the cell rejoins the broken ends successfully (by Nonhomologous End-Joining) and all is well. However, occasional failures can result in changes in the structure of the chromosome.

Insertions and Deletions (Indels)

Extra base pairs may be added (insertions — LINK) or removed (deletions — LINK) from the DNA of a gene. The number can range from one to thousands. Collectively, these mutations are called indels.

Duplications

Duplications are a doubling of a section of the chromosome. During meiosis, crossing over between sister chromatids that are out of alignment can produce one chromatid with a duplicated segment and the other with a corresponding deletion. MORE

Translocations

Karyotype analysis can also reveal translocations between chromosomes.

Translocations are the transfer of a piece of one chromosome to a nonhomologous chromosome.

Translocations are often reciprocal; that is, the two nonhomologues swap segments.

Translocations can alter the phenotype is several ways:

- The break may occur within a gene destroying its function.

- Translocated genes may come under the influence of different promoters and enhancers so that their expression is altered. The t(8;14) translocation in Burkitt's lymphoma (figure) is an example. [More]

- The breakpoint may occur within a gene creating a hybrid gene. This may be transcribed and translated into a protein with an N-terminal of one normal cell protein coupled to the C-terminal of another.

Examples

-

The Philadelphia chromosome (Ph1) found so often in the leukemic cells of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is the result of a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 which produces a compound gene (BCR-ABL). More

- a translocation between chromosomes 18 and 14 causes B-cell leukemia [Link]

Aneuploidy — the gain or loss of whole chromosomes — is the most common chromosome abnormality. Cancer cells are frequently aneuploid. Aneuploidy is caused by nondisjunction, the failure of chromosomes to correctly separate:

Zygotes missing one chromosome ("monosomy") cannot develop to birth (except for females with a single X chromosome).

Three of the same chromosome ("trisomy") is also lethal to the developing fetus except for chromosomes 13, 18, and 21 (trisomy 21 is the cause of Down syndrome).

Three or more X chromosomes are viable because all but one of them are inactivated. [Link to discussion]

18 December 2023

Location of the gene for muscle glycogen phosphorylase on human chromosome 11

Location of the gene for muscle glycogen phosphorylase on human chromosome 11

Location of the gene for muscle glycogen phosphorylase on human chromosome 11

Location of the gene for muscle glycogen phosphorylase on human chromosome 11