| Index to this page |

The biological control of pests involves using natural enemies of the pest to control it — instead of chemical agents like insecticides and herbicides. Not only should this be safer for the environment, but — once established — the natural enemies might be able to sustain their population avoiding the need for future treatments.

Most of the species that we consider pests are plants ("weeds") or animals (especially insects) that have invaded a new habitat without being accompanied by the natural enemies that kept them in check in their original home. With increasing international travel and trade, this problem becomes increasingly severe.

In 1887, this insect — an import from Australia — was devastating the citrus groves of California. A U.S. entomologist went to Australia to find a natural enemy and came back with the vedalia beetle, a species of lady beetle. Released in California, the beetle quickly brought the scale under control.

At least until 1946. In that year the pest made a dramatic comeback. This coincided with the first use of DDT in the groves. DDT not only killed the target pest insects but the vedalia beetle as well.

Only by altering spray procedures and reintroducing the beetle was the scale insect again controlled.

Prior to its eradication from the southeastern United States, the screwworm was causing huge annual livestock losses.

The sterile male technique involves releasing factory-reared and sterilized flies into the natural population. Sterilization is done by exposing the factory flies to just enough gamma radiation to make them sterile but not enough to reduce their general vigor.

Starting in early 1958, up to 50 million sterilized flies were released each week from aircraft flying over Florida and parts of the adjoining states.

Each time a fertile female in the natural population mated with a sterile male, the female layed sterile eggs. Since the females mate only once, her reproductive career was at an end. By early 1959, the pest was totally eliminated east of the Mississippi River.Success depended only on the sterile males. In fact, the presence of sterile females was a drawback (because they competed with the intended target), but it was difficult to separate the sexes.

The southwestern states presented a harder problem because the fly winters in Mexico and with each new season could move across the border. Even so, by expanding the program to include Mexico as well, the screwworm fly was finally eliminated from both countries by 1991.

The sterile male technique has also been used with success against several other insect pests, includingGenetic engineering may solve both these problems.

A group of British entomologists (see Thomas, D. D., et al., in the 31 March 2000 issue of Science) have engineered Drosophila so that

The system works like this.

| Link to more information on response elements (REs). |

In 2010, release of male mosquitoes — Aedes aegypti, the vector of several viral diseases including yellow fever and dengue fever — genetically modified (GM) with a similar system reduced the resident mosquito population in part of Grand Cayman (Caribbean) by 80%. In May of 2021, these GM mosquitoes began to be released in the Florida Keys.

Techniques have now been developed which greatly increase the frequency of any desired gene in a population. So far, the uncertainties of quickly spreading an engineered gene through an entire wild population has kept the process strictly confined to the laboratory. The process, called gene drive or the mutagenic chain reaction, is described on a separate page — Link to it.

Insect sex attractants have also been enlisted in the fight against harmful insects.

Distributing a sex attractant throughout an area masks the female's own attractant so the sexes fail to get together. This is called "communication disruption" or "male confusion".

In some cotton-growing areas, male confusion with the sex attractant of the pink bollworm reduced the need for conventional chemical insecticides by 90%.

It has been used successfully against pests that attack tomatoes, grapes, and peaches.

| Discussion of sex attractants and their use in male confusion. |

| Link to more information on the uses to which Bt and its toxin are being put. |

Introduced into Australia, this cactus soon spread over millions of hectares of range land driving out forage plants.

In 1924, the cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum, was introduced (from Argentina) into Australia.

The caterpillars of the moth are voracious feeders on prickly-pear cactus, and within a few years, the caterpillars had reclaimed the range land without harming a single native species.

However, its introduction into the Caribbean in 1957 did not produce such happy results. By 1989, the cactus moth had reached Florida, and now threatens 5 species of native cacti there.

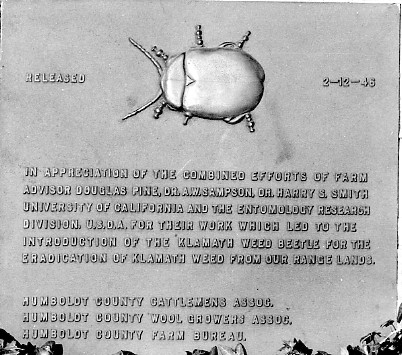

In 1946 two species of Chrysolina beetles were introduced into California to control the Klamath weed (also known as St. Johnswort, and the same plant that yields the popular herbal concoction) that was ruining millions of acres of range land in California and the Pacific Northwest. Before their release, the beetles were carefully tested to make certain that they would not turn to valuable plants once they had eaten all the Klamath weed they could find.

The beetles succeeded beautifully, restoring about 99% of the endangered range land and earning them a commemorative plaque at the Agricultural Center Building in Eureka, California. (Photo courtesy of John V. Lenz.)

| Welcome&Next Search |