| Index to this page |

Dendritic cells (DCs) get their name from their surface projections (that resemble the dendrites of neurons).

They are found in most tissues of the body and are particularly abundant in those that are interfaces between the external and internal environments (e.g., skin, lungs, and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract) where they are ideally placed to encounter extrinsic antigens, including those expressed by invading pathogens.

|

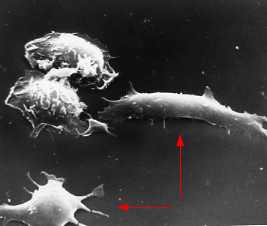

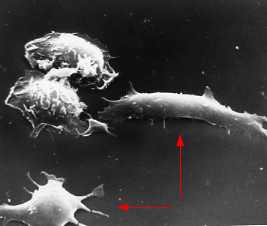

| Two dendritic cells (arrows) from the spleen of a mouse. Compare their smooth surface with that of the two macrophages visible at the upper left. (Courtesy of Ralph Steinman, from R. M. Steinman et al., J. Exp. Med. 149:1, 1979.) |

In either case, the ingested antigens are degraded in lysosomes into peptide fragments that are then displayed at the cell-surface nestled in class II MHC molecules [Link].

Having ingested antigen in the tissue, they migrate to lymph nodes and spleen where they can meet up with T cells bearing the appropriate T-cell receptor for antigen (TCR).

What happens next depends on the nature of the antigen.The importance of dendritic cells in developing immunity to pathogens is dramatically shown in those rare infants who lack a functioning gene needed for the formation of dendritic cells. They are so severely immunodeficient that they are at risk of life-threatening infections.

What accounts for the activation of dendritic cells by foreign antigens but not by self antigens?

Pathogens, especially bacteria, have molecular structures thatExamples:

Dendritic cells have a set of transmembrane receptors that recognize different types of PAMPs. These are called Toll-like receptors (TLRs) because of their homology to receptors first discovered and named in Drosophila.

TLRs identify the nature of the pathogen and turn on an effector response appropriate for dealing with it. These signaling cascades lead to the expression of various cytokine genes.

While all DCs share certain features, they actually represent a variety of cell types with different differentiation histories, phenotypic traits and, as outlined above, different effector functions.

Examples:

Conventional dendritic cells are also called Myeloid Dendritic Cells (mDCs). As that name implies, these cells are derived from the same myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow that give rise to granulocytes and monocytes [View].

In humans, the majority of our cDCs belong to a subset designated conventional type 1 dendritic cells (cDC1). They present antigen to T cells and activate the T cells by secreting large amounts of IL-12 [View]. They are the major stimulators of Th1 helper T cells.

Conventional DC1 cells express the toll-like receptorsConventional DC1 cells can present antigen not only to CD4+ T cells but also to CD8+ T cells (cross-presentation).

These cells ("pDCs") get their name from their extensive endoplasmic reticulum which resembles that of plasma cells. However, unlike plasma cells that are machines for pumping out antibodies, pDCs secrete huge amounts of interferon-alpha especially in response to viral infections.

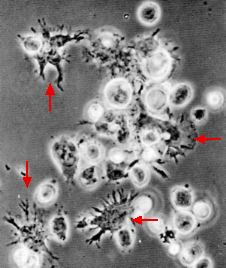

Plasmacytoid DCs have internal toll-like receptors: | Phase contrast micrograph of spleen cells after 2 days in culture. Four dendritic cells (arrows) can be seen clustered with lymphocytes. (Courtesy of Ralph Steinman from K. Inaba et al., J. Exp. Med. 160:858, 1984.) |

Ralph Steinman, the pioneer in the study of dendritic cells, has provided striking visual evidence of the cellular interactions between antigen-presenting dendritic cells, T cells, and B cells. When spleen cells are cultured with antigen, tight clusters of cells form (see figure). The clustering occurs in two phases:

Some dendritic cells not only activate T cells to respond to a particular antigen but tell them where to go to deal with that antigen.

Two examples:

| * How, one might ask, can dendritic cells in the internal environment engulf microbes, etc. out on the surface of the skin? It turns out that these dendritic cells, called Langerhans cells, extend protrusions that penetrate the tight junctions between the epithelial cells above them and use these to take in surface antigens for processing. |

(In telling this story, I cannot help being reminded of the way that scout bees, having found food, return to the hive and tell the worker bees there where to go to find it! [Link])

Most vaccines are given by injection into muscle or skin. This works very well for inducing systemic immunity; that is, IgG antibodies in the blood able to attack pathogens (e.g., tetanus) that are present in the blood.

Injected vaccines do not work as well for illnesses caused by intestinal pathogens such as| Welcome&Next Search |