Translocation of Food

Food and other organic substances (e.g., some plant hormones and even messenger RNAs [Link]) manufactured in the cells of the plant are transported in the phloem.

- Sugars (usually sucrose),

- amino acids, and

- other organic molecules

enter the sieve elements through plasmodesmata connecting them to adjacent companion cells.

Once within the sieve elements, these molecules can be transported either up or down to any region of the plant moving at rates as high as 110 μm per second.

Two demonstrations:

- Girdling. Girdling is removing a band of bark from the circumference of the tree. Girdling removes the phloem but not the xylem.

If a tree is girdled in summer, it continues to live for a time. There is, however, no increase in the weight of the roots, and the bark just above the girdled region accumulates carbohydrates.

Unless a special graft is made to bridge the gap, the tree eventually dies as its roots starve.

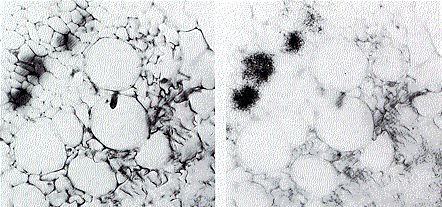

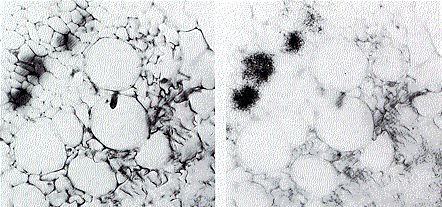

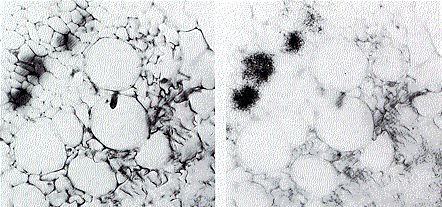

- The photos (courtesy of R. S. Gage and S. Aronoff) are autoradiographs showing that the products of photosynthesis are transported in the phloem. A cucumber leaf was supplied with radioactive water (3HOH) and allowed to carry on photosynthesis for 30 minutes. Then slices were cut from the petiole of the leaf and covered with a photographic emulsion. Radioactive products of photosynthesis darkened the emulsion where it was in contact with the phloem (upper left in both photos), but not where it was in contact with the xylem vessels (center). In the photomicrograph on the left, the microscope is focused on the tissue in order to show the cells clearly; on the right, the microscope has been focused on the photographic emulsion.

Some fruits, such as the pumpkin, receive over 0.5 gram of food each day through the phloem. Because the fluid is fairly dilute, this requires a substantial flow. In fact, the use of radioactive tracers shows that substances can travel through as much as 100 cm of phloem in an hour.

What mechanism drives the translocation of food through the phloem?

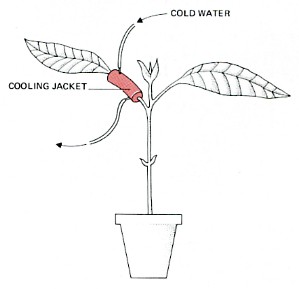

Translocation through the phloem is dependent on metabolic activity of the phloem cells (in contrast to transport in the xylem).

Translocation through the phloem is dependent on metabolic activity of the phloem cells (in contrast to transport in the xylem).

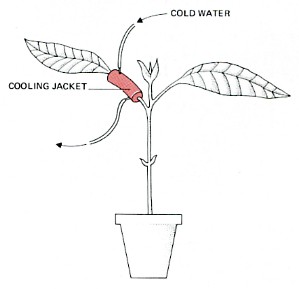

- Chilling its petiole slows the rate at which food is translocated out of the leaf (right).

- Oxygen lack also depresses it.

- Killing the phloem cells puts an end to it.

The Pressure-Flow Hypothesis

The best-supported theory to explain the movement of food through the phloem is called the pressure-flow hypothesis.

Thus it is the pressure gradient between "source" (leaves) and "sink" (shoot and roots) that drives the contents of the phloem up and down through the sieve elements.

Thus it is the pressure gradient between "source" (leaves) and "sink" (shoot and roots) that drives the contents of the phloem up and down through the sieve elements.

Tests of the theory

1. The contents of the sieve elements must be under pressure.

This is difficult to measure because when a sieve element is punctured with a measuring probe, the holes in its end walls quickly plug up. However, aphids can insert their mouth parts without triggering this response.

Left: when it punctures a sieve element, sap enters the insect's mouth parts under pressure and some soon emerges at the other end (as a drop of honeydew that serves as food for ants and bees).

Right: honeydew will continue to exude from the mouthparts after the aphid has been cut away from them. (The photos are the work of the late Martin H. Zimmerman and were provided by him.)

2. The osmotic pressure of the fluid in the phloem of the leaves must be greater than that in the phloem of the food-receiving organs such as the roots and fruits. Most measurements have shown this to be true.

Plant scientists at the Davis campus of the University of California (reported in the 13 July 2001 issue of Science) have demonstrated that messenger RNAs can also be transported long distances in the phloem. They grafted normal tomato scions onto mutant tomato stocks and found that

- mRNAs synthesized in the stock were transported into the scions.

- These mRNAs converted the phenotype of the scion into that of the stock.

3 September 2014

Translocation through the phloem is dependent on metabolic activity of the phloem cells (in contrast to transport in the xylem).

Translocation through the phloem is dependent on metabolic activity of the phloem cells (in contrast to transport in the xylem).